Black Women in Entertainment

How the black radical female artists of the ’60s and ’70s made art that speaks to today’s politics

In scale, it is small — barely 18 inches tall — but its message couldn’t have been more explosive when Los Angeles artist Betye Saar turned a vintage California wine jug, with a label featuring a handkerchief-bedecked mammy, into a sculpture of a Molotov cocktail. Imprinted on the bottle is a black power fist. It’s degrading kitsch remade into fiery cultural armament.

The 1973 sculpture, part of “We Wanted a Revolution: Black Radical Women, 1965-85,” which opened at the Brooklyn Museum in April and is now at L.A.’s California African American Museum, had not been on public view since Saar made it 44 years ago.

“Liberation of Aunt Jemima: Cocktail,” as the piece is titled, was one of a series of works in which Saar weaponizes — figuratively, at least — racially charged black collectibles, often smiling mammy figures who brandish pistols or grenades. In the case of “Liberation of Aunt Jemima: Cocktail,” the entire vessel takes on the guise of a weapon.

“I wanted to empower her,” Saar said of Aunt Jemima in 2015, referring to another of her pieces. “I wanted to make her a warrior.”

The display of Saar’s Molotov cocktail sculpture represents a keen bit of sleuthing by the show’s co-curators, Catherine Morris and Rujeko Hockley of the Brooklyn Museum (Hockley is now at the Whitney Museum of American Art).

Morris came across a parenthetical reference to it in a feminist art journal. But no photos or other documentation existed. Intrigued, the curators checked with Saar’s studio, but the piece had been out of her hands since the ’70s. Saar, though, keeps records of all her transactions. By combing through old ledgers, the curators tracked “Cocktail” to the SoHo home of a lawyer who used to work for Saar.

“It’s been there since the ’70s,” Hockley says. “That was a special moment.”

“And the Brooklyn Museum was subsequently able to acquire it,” Morris adds. “I’m totally thrilled about that.”

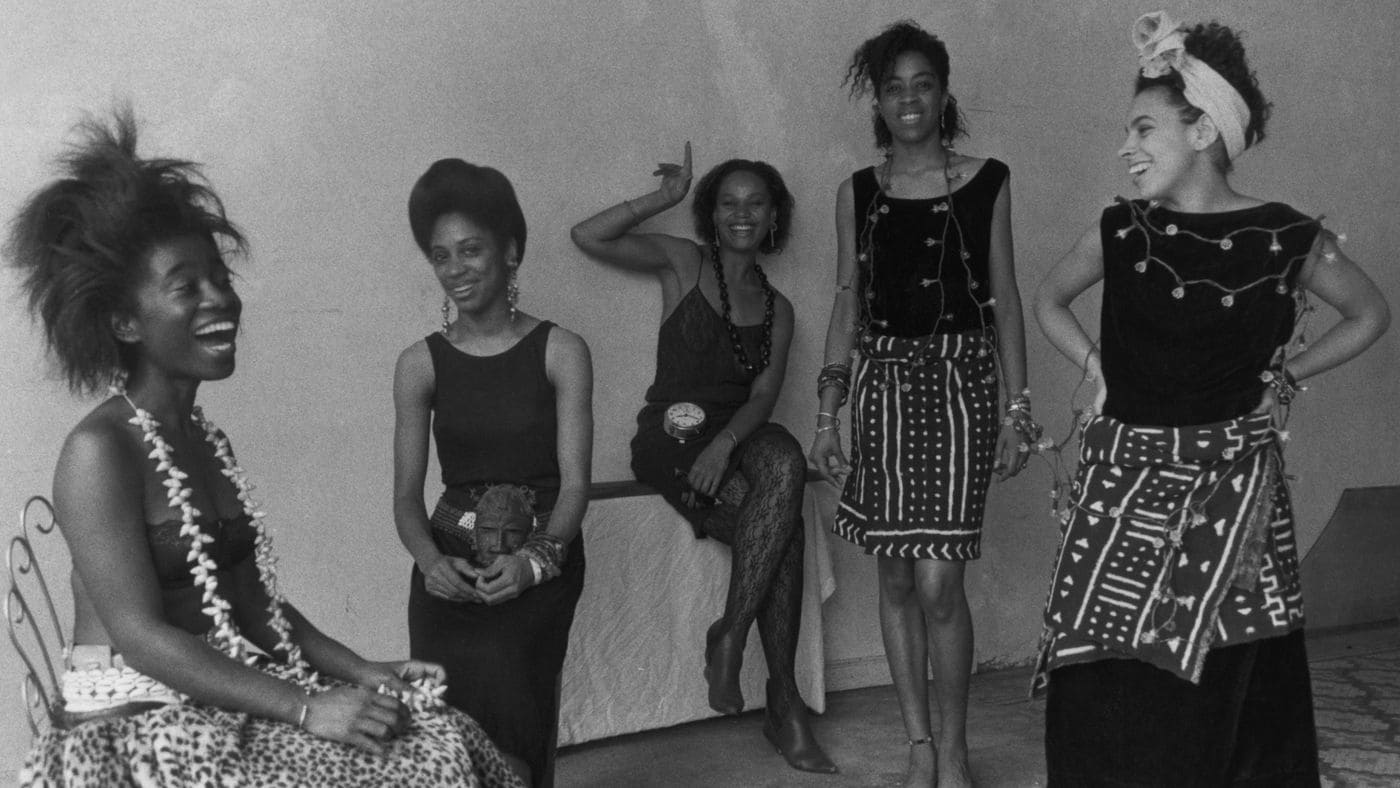

“We Wanted a Revolution” has unearthed all manner of important works from personal archives, private collections and other arts spaces. This includes the understated architectonic sculptures of Beverly Buchanan; outfits by Jae Jarrell, whose work straddled the line between fashion and art; and prints and collages by Kay Brown, who along with five other artists in 1971 helped organize a key New York exhibition of art by black women titled “Where We At.”

“The title,” Brown later wrote, “depicted the significant role of the Black woman artist and showed the community that we did exist — in numbers.”

“We Wanted a Revolution” shines a spotlight on those numbers and on the conditions under which African American women artists labored in the ’60s, ’70s and ’80s.

All of it points to the unique issues black women artists faced (and continue to face) as women and artists in a society in which race plays a defining role.

“Black women were trying to find room for themselves as women, as black, as artists, as activists and how to manage and deal with all of those things,” Morris says. “The question was, do you align yourselves with the black power movement and deal with sexism in that context? Do you align yourself with feminism and deal with racism in that context? There is always a battle to be fought.”

The exhibition began as a way to mark the 10th anniversary of the Brooklyn Museum’s Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art, where Morris serves as senior curator.

“The Sackler Center houses ‘The Dinner Party,’ one of the iconic pieces of second wave feminism,” says Morris, referring to Judy Chicago’s 1970s installation that presents world history from a female (anatomical) perspective. “Judy’s piece is revisionist history. So it’s time to take a look at the history of feminism and revise that as well.”

The Sackler, Hockley says, “hasn’t really grappled with race and class and with all of the facets of individual experience. So one of the things we wanted to do for this anniversary was say, ‘Hey, let’s talk about it.’”

The discussion couldn’t…

Please read original article- How the black radical female artists of the ’60s and ’70s made art that speaks to today’s politics