Black Women in Science

Celebrating Black Women Scientists

In our continuing coverage celebrating Black History Month, discover some of the lesser-known African-American women scientists who have made groundbreaking impacts in their respective fields.

NASA’s “human computers” Katherine Johnson, Mary Jackson, and Dorothy Vaughan made their way into our hearts via the blockbuster film Hidden Figures, but there are so many other fantastic black women scientists that deserve the spotlight. To celebrate Black History Month, here are a few more amazing women who have carved out their own place in science.

Alice Ball (Chemist)

Alice Augusta Ball was born on July 24, 1892 in Seattle, Washington to Laura, a photographer, and James P. Ball, Jr., a lawyer. Ball earned undergraduate degrees in pharmaceutical chemistry (1912) and pharmacy (1914) from the University of Washington. In 1915, Ball became the very first African American and the very first woman to graduate with a M.S. degree in chemistry from the College of Hawaii (now known as the University of Hawaii). She was also the very first woman chemistry instructor at the same institution.

Ball worked extensively in the laboratory to develop a successful treatment for those suffering from Hansen’s disease (leprosy). Her research led her to create the first injectable treatment using oil from the chaulmoogra tree, which up until then, was only a moderately successful topical agent that was used to treat lesprosy in Chinese and Indian medicine. Ball’s scientific rigor resulted in a highly successful method to alleviate leprosy symptoms, later known as the “Ball Method,” that was used on thousands of infected individuals for over 30 years until sulfone drugs were introduced. Tragically, however, Ball died on December 31, 1916 at the young age of 24 after complications resulting from inhaling chlorine gas in a lab accident. During her brief lifetime, she did not get to see the full impact of her discovery.

Also, it was not until six years after her death, in 1922, that Ball got the proper credit she deserved. Up until that point, the president of the College of Hawaii, Dr. Arthur Dean, had taken full credit for Ball’s work. Unfortunately, it was commonplace for men to take the credit of women’s discoveries and Ball fell victim to this practice (learn about three more women scientists whose discoveries were credited to men). She was also all but forgotten from scientific history for more than 80 years. Then, in 2000, the University of Hawaii-Manoa honored Ball by placing a bronze plaque in front of a chaulmoogra tree on campus and former Lieutenant Governor of Hawaii, Mazie Hirono, declared February 29 “Alice Ball Day.” In 2007, the University of Hawaii posthumously awarded her with the Regents’ Medal of Distinction.

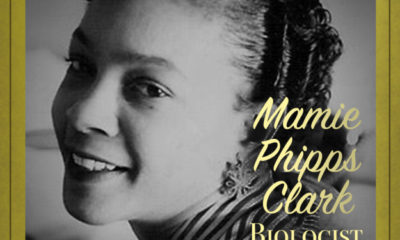

Mamie Phipps Clark (Social Psychologist)

Mamie was born on April 18, 1917 in Hot Spring, Arkansas to Harold H. Phipps, a physician, and Katy Florence Phipps, a homemaker. She received several scholarship opportunities and chose to attend Howard University in 1934 as a math major minoring in physics. There she met Kenneth Bancroft Clark, a master’s student in psychology, who later became her husband and who convinced her to pursue psychology due to her interests in child development. In 1938, Clark graduated magna cum laude from Howard University and went on to pursue her master’s in psychology there and later, her PhD from Columbia University. In 1943, Clark became the first black woman to earn a psychology doctorate from Columbia.

Clark’s research focused on defining race consciousness among young children. Her now infamous “Dolls Test” provided scientific evidence that was influential in Brown v. Board of Education (1954). In this test, over 250 black children ages 3-7, about half who attended segregated schools in the South (Arkansas) and about half who attended racially mixed schools in the northeast (Massachusetts), were asked to provide their preferences for dolls (brown skin with black hair or white skin with yellow hair). Their findings from the “Dolls Test” showed that the majority of black children wanted to play with the white doll (67%), indicated that the white doll was the “nice” doll (59%), indicated that the brown doll looked “bad” (59%), and chose the white doll as having the “nice color” (60%). Black children from the racially mixed northern schools felt more outward turmoil about the racial injustices this experiment revealed than those in the segregated Southern schools who felt more internalized passivity about their inferior racial status. Clark and her research team …

Read More- Celebrating Black Women Scientists