Black Women in Education

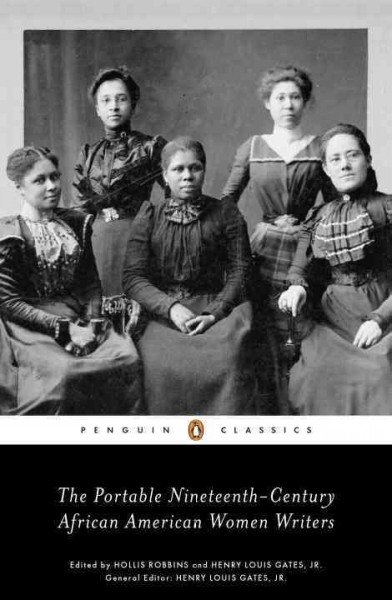

A ‘Portable’ Overview Of A Complex, Compelling History

Mary Prince’s story is, in some ways, a familiar narrative. Born a slave around 1788, she was abused by a mistress, Mrs. Wood — beaten, forced to work when ill, refused the chance to buy her freedom. Eventually, she sought emancipation on English soil. When she declares “All slaves want to be free — to be free is very sweet,” it feels of a piece with the general story we, as a nation, are told about black women in the 19th century: downtrodden, then free.

But as excerpted in The Portable Nineteenth-Century African American Women Writers, Prince’s biography offers much more complexity. Prince marries a free man, a situation the Woodses can’t quite reconcile; her emancipation begins with the Woods kicking her out in a fit of pique. The account, published by her employer Mr. Pringle, made Pringle the object of a libel suit and brought Prince to court. And in this excerpt, Prince delivers a pointed rebuke to anyone who believes that era’s dominant narrative, “that the slaves do not need better usage, and do not want to be free.”

I talk a lot about books being “in conversation.” Sometimes the links are clear — The Portable Nineteenth-Century African American Women Writers is in conversation with anthologies of black or 19th-century literature that sideline these women. It’s also in conversation with cultural studies like Beyond Respectability, which discusses the work of many women who appear here: Fannie Barrier Williams, Anna Julia Cooper, Mary Church Terrell.

But Nineteenth-Century African American Woman Writers is also in conversation with itself — and against that dominant narrative. Editors and professors Henry Louis Gates, Jr. and Hollis Robbins have assembled an incisive collection of pieces by over 50 women, spanning nearly a century of written work, and highlighting the importance of such narratives in trying to illuminate the past. Mary Prince’s cry for emancipation isn’t just part of a tidy story of slavery and freedom — it’s part of a complex and compelling whole.

Though this is a book meant to be referenced rather than devoured, almost any selection makes for absorbing reading, and as a whole they cover a breadth of tone and experience that defies a neat history. Some aspects of its overarching narrative are universal — every woman here is pushing for further freedom and visibility of black women, no matter their current legal position — but even then, the approaches are tellingly varied. (The academic remove of Northern-born abolitionist Sarah Parker Remond sits alongside the visceral recollections of ex-slave Louisa Picquet.)

That variety makes for a wide map of American-American womanhood before and after the Civil War. Some excerpts hint at an increasing influence in cultural spheres: Eliza Potter wrote the tell-all A Hairdresser’s Experience in High …

Please read original article – A ‘Portable’ Overview Of A Complex, Compelling History